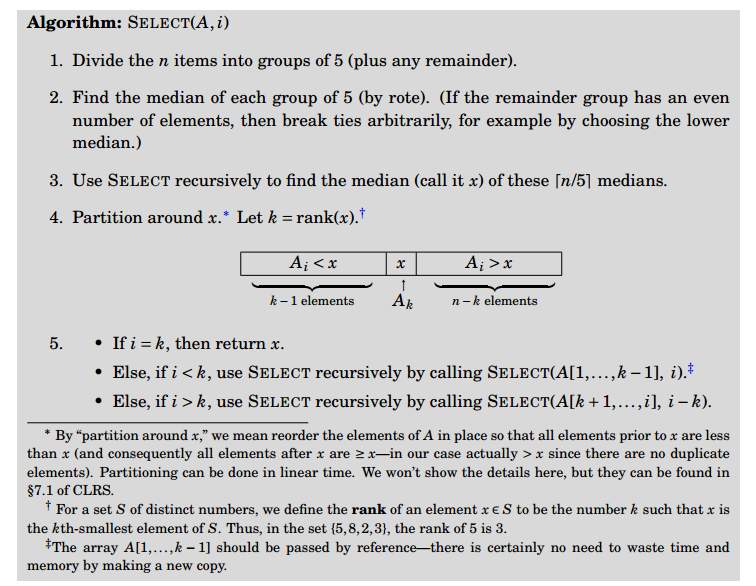

The goal of the QuickSelect algorithm is simple: quickly select the \(k^{th}\) smallest element in an

unsorted array of \(n\) elements. Note that the \(({n \over 2})^{th}\) smallest element is the median.

Lucky for me, a detailed explanation of how the algorithm works has already been

provided by MIT in this really good picture, so I don’t need to explain that at

all!

After we split the array into groups of five, if the number of elements in the array, \(n\), is not a

multiple of five, there will be one group at the end that does not have five elements. Let’s call

this group the “remainder group”.

So, for an array of \(n\) elements, there are at least \(ceil({n \over 5}) - 1\) non-remainder groups

of 5. This is because if \(n\) is not a multiple of 5, there will be exactly \(ceil({n \over 5}) - 1\) non-remainder

groups of 5 and one remainder group of less than 5 elements. If \(n\) is a multiple of 5, then there

will be exactly \(ceil({n \over 5}) = {n \over 5}\) groups of 5 without a remainder group left over.

Now that we have our groups of 5, let’s sort each of them separately. Since each of these groups contains

exactly 5 elements, a constant number of elements, running a sorting algorithm on each will take

constant time \(O(1)\). So, if we are doing an operation that’s \(O(1)\) for \(n \over 5\) groups, then

sorting all of those groups will take \(O(n)\). Once all the 5-element subgroups are sorted, let’s

make a set of all their medians.

Now we’re going find the median of medians by calling QuickSelect recursively on our set of medians.

Since there were \(n \over 5\) groups of 5 elements, there are also \(n \over 5\) medians from which to find the median of medians. Therefore using QuickSelect recursively on our set of medians will take \(T({n \over 5})\). Let’s

remember that for our recurrence relation much later and for now just assume we have the median of medians.

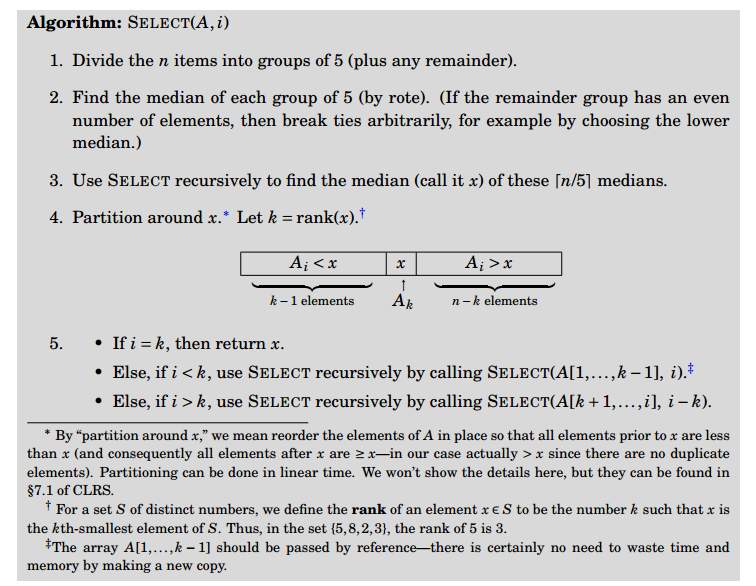

With our median of medians that we just got, we’re going to partition the array just like we did in

QuickSort, using the median of medians as the pivot: we’re going to put all elements less than the

pivot to its left and all elements greater than it to its right. If you don’t remember how that’s done

take a look at the notes on QuickSort. At this point we’ve got the array partitioned as shown in

the first diagram, so all that remains is the recurive call. But to figure out the Big-O of the recursive

call, we have to figure out the size of the sub-array we’re going to call QuickSelect on recursively.

Remember that we are using QuickSelect to get us the \(k^{th}\) smallest element. So, if after

partitioning using the median of medians, the position \(p\) of our pivot is greater than k, we clearly

have to call Quicksort on the subarray that’s less than the pivot (realize that the pivot is both at

position \(p\) and is the \(p^{th}\) smallest element since we partitioned around it). Converserly,

if, after partitioning, \(p\) is less than k, we have to call Quicksort on the subarray that’s greater

than the pivot – but now we’re looking for the \({(p-k)}^{th}\) element in that subarray since all the

elements in the subarray are greater than the \(p^{th}\) smallest element in our original array and we

were looking for the \(k^{th}\) smallest element in our original array.

So, now that we understand something about how we’ll call QuickSelect recursively on one of the two

subarrays, how do we put an upper bound on their size that’s useful for a recurrence relation so

that we can calculate QuickSelect’s Big-O? Realize that putting an upper bound on the size of these

subarrays is equivalent to putting an upper bound on the number of elements that are greater than or less

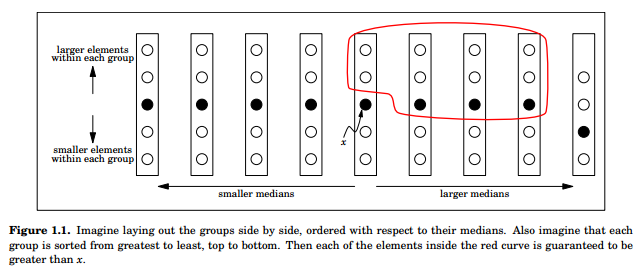

than the median of medians. Let’s start with another great picture from MIT to get us all using the same

visualization:

Recall that the total number of 5 element groups, including the remainder group, is \(ceil({n \over 5})\). Notice that

half of those groups can have medians that are greater than the median of medians. Well, it’s

not quite half. If there are an odd number of groups then it would actually be the rounded-down

version of half so let’s say that there are at least \(floor({1 \over 2} ceil({n \over 5}))\) groups of 5 elements

whose median is greater than the median of medians. Well, it’s not quite that number either, since

we shouldn’t count the group that actually contains the median of medians. So there are

\(floor({1 \over 2} ceil({n \over 5})) - 1\) groups with medians larger than the median of medians.

So, what then is the minumum number of elements (not groups) that are greater than the median of

medians? Well for each group whose median is greater than the median of medians, there are at least

3 elements that are greater than the median of medians. So, you’d figure that it would be 3 times

the expression we got at the end of the last paragraph. The only problem is that the expression

included the remainder group, which may not even have 3 elements, let alone 3 greater the median

of medians. So the answer is actually 3 times one less than that expression, or written in math:

\(3(floor({1 \over 2} ceil({n \over 5})) - 2)\). Oh! We almost forgot the two elements in the same

group as the median of medians that are greater than it. So our final expression for the minimum

number of elements greater than the median of medians is \(3(floor({1 \over 2} ceil({n \over 5})) - 2) + 2\). By

algebra we can show that this is greater than \({3 \over 10} n - 6\).

Alright, we managed to put a lower bound on the number of elements that are greater than the median

of medians, and this lower bound could just as easily apply to the number of elements that are

less than the median of medians too. So really, we put a lower bound on the size of the two

subarrays that we’ll be calling Quicksort on recursively. What’s more, for any expression of \(n\)

that defines a lower bound on the size of the subarrays, \(n\) minus that expression defines an

upper bound! So we finally have our upper bound on the size of these subarrays, and it’s

\(n - {3 \over 10} n - 6\ =\ {7 \over 10} n + 6\).

Therefore, the recurrence relation of Quicksort is \(T(n) = T(ceil({n \over 5})) + T({7 \over 10}n + 6) + O(n)\).

By some sneaky involved math (proof by the Substitution Method), that recurrence relation solves

to \(T(n) = O(n)\). For more information, check out this document from which I stole all the

diagrams and reasonings.

You don’t really need all that to get a quick and dirty intuition of how QuickSelect, a recursive algorithm, runs in linear time. The whole long blurb above basically just serves as proof of two things:

But most people are willing to just accept that there’s some fancy method that’s able to get something close to the median in linear time and that the actual interesting part of QuickSelect is why that means QuickSelect as a whole runs in linear time.

So what I’m going to show here is that if we can assume that finding the median takes linear time and rearranging using the median as pivot takes linear time then it’s actually pretty clear that QuickSort also takes linear time. I’ll then leave it to you to convince yourself that you can in fact get something quantifiably close enough to the median in linear time so that the intuition I’ll now provide still holds.

So given our two assumptions, why is QuickSelect \(O(n)\)? Well let’s run through it’s execution.

First we get the median in \(O(n)\) and rearrange the array into two subarrays using the median as pivot in \(O(n)\). Two operations that are \(O(n)\) is still \(O(n)\). The \(k^{th}\) smallest element will be in one of the two subarrays so we’ll repeat on one of the subarrays. Since the pivot is the perfect median the subarrays are of size exactly \(n \over 2\). Therefore the next round of median finding and rearranging is going to be \(O({n \over 2})\). If we have to recurse again then the next round will be \(O({n \over 4})\). I think you get the idea. This is a geometric whose value we know:

\[ n\ +\ \sum_{i=1}^{\infty} {1 \over {2^i}}\ =\ n\ +\ n\ =\ 2 n\ =\ O(n) \]